In 1997, a storm sent five million pieces of Lego into the ocean. A U.K. beachcomber helped build a citizen science project that aims to track those pieces and tell a story about plastic pollution.

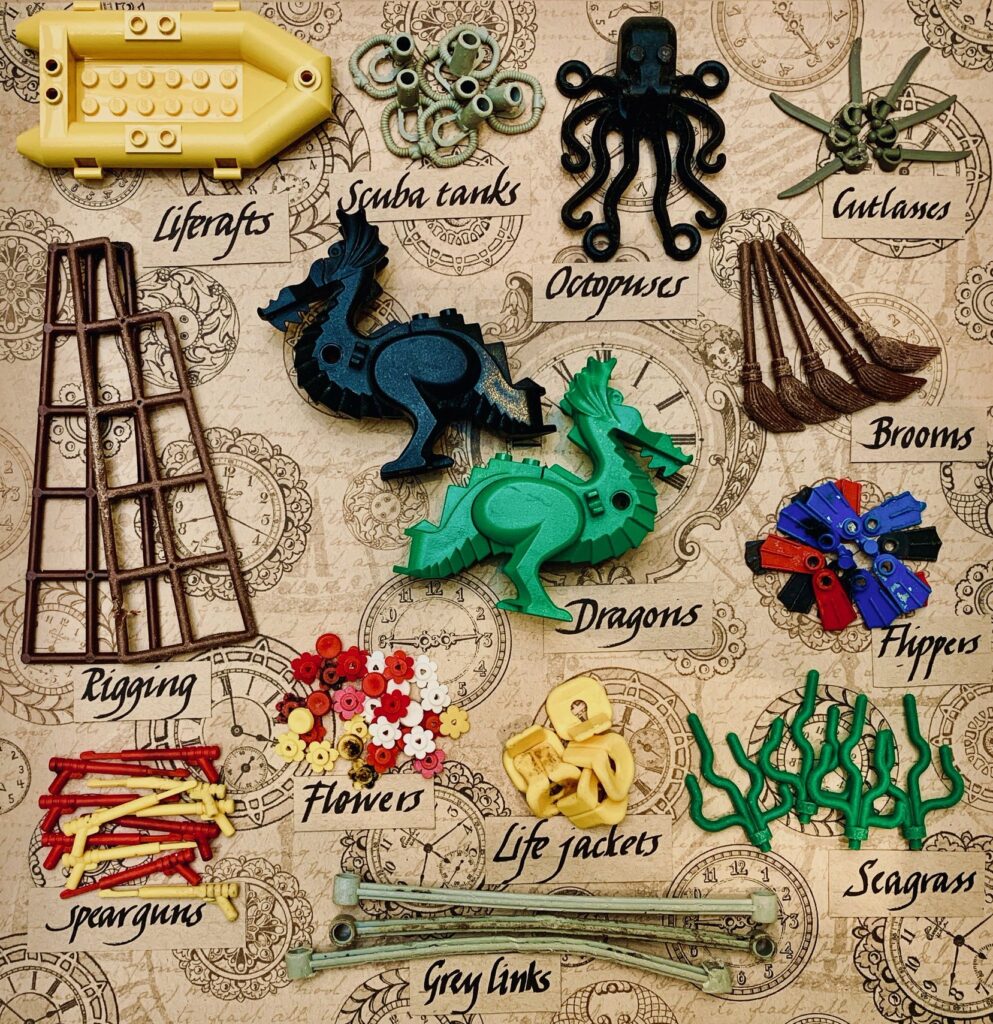

On February 13, 1997, a huge storm near the coast of Cornwall, UK, pushed sixty-two containers off the cargo ship Tokio Express. One of these containers held five million pieces of the popular children’s toy, Lego. Coincidentally, many of the Lego pieces were ocean-themed — octopuses, sharks, mermaids, and, ironically, life jackets. Twenty-six years later, the pieces are still turning up all over the Northern Hemisphere, in locations as diverse as Galveston Island, Texas, the coastal town of Zandvoort in the Netherlands, and Tracey Williams’ favorite beachcombing spot in Cornwall, UK.

Williams recalls that, when she was in her early twenties at the beginning of the 1980s, she’d watch storms at sea from her family home in Devon, and her father would say “the sea will provide.” Twenty years later, delivering pieces of Lego to Williams’ beach, the sea provided her with an opportunity to make a difference. Williams is the founder of Lego Lost At Sea, a project that combines citizen science, Anthropocene archaeology, oceanography, design, and community awareness to address the issue of plastic pollution in the ocean.

Williams, a seasoned beachcomber, first noticed the Lego pieces soon after the ’97 spill. It started as a fun treasure hunt with her children. Then others got excited too — the black octopus and the rare green dragons were particularly popular pieces among British beachcombers, creating something of a dragon-hunting craze. Williams still gets an annual Christmas card from a former neighbor who signs herself “Mary, keeper of the green dragon.”

Williams moved inland and forgot about the spill until moving back to Cornwall in 2010 and finding a Lego life jacket during a beach walk. Curious that the pieces were still turning up thirteen years later, she created a Facebook page, Lego Lost At Sea, to document her finds and invite others to share theirs. The page now has 75,000 members.

Annually, at least fourteen million tons of plastic enter the ocean, accounting for eighty percent of marine debris. Some plastic items are, like the Lego, from cargo spills, but many arrive in other odd ways. Kids, for instance, have flushed two-and-a-half million Lego bricks down toilets.

Lego Lost At Sea has become more than a treasure hunt: it’s now a resource for scientists studying ocean movements and plastic pollution. (Some 51,800 sharks — along with other Lego pieces — remain lost in the ocean.) The project won the Current Archaeology Rescue Project of the Year award in 2023. It also has a BBC Podcast and has resulted in a book by Williams called Adrift, The Curious Tale of the Lego Lost at Sea, which she wrote with oceanographer Dr. Curtis Ebbesmeyer, who has tracked the Lego spill since 1997 to study ocean currents.

“Ultimately it opened my eyes to the rest of the plastic in the sea and sand,” Williams says. “When your eyes are down, searching, you start to notice the rest of the debris polluting the coastal environment.” When Williams first started picking up plastic items from beaches, she assumed that their presence was fairly recent. “But the more you delve into it, the more you realize how long some of the plastic has been lying at the bottom of the sea or buried in sand,” she says. “Some of the plastic we pick up is sixty to seventy years old — toothbrushes, curtain rings, bottles.”

And some may remain there for over a thousand years.

A study published in July of 2020 shows that ocean-battered Lego pieces could take almost 1,300 years to degrade. Dr. Andrew Turner, Reader in Environmental Sciences at the University of Plymouth, UK, collaborated with Williams and calls her project “valuable citizen science.” For the study, he paired fifty pieces of weathered Lego from the spill with unweathered sets purchased in the 1970s and ’80s to determine their endurance in the marine environment. The result (1,000–1,300 years to degrade) was shocking. The timeline for degradation would be the same for any rigid plastic, he says. “Food containers, PET bottles, water bottles designed to be long-term are … going to last thousands of years. The area of the ocean [makes up] seventy percent of the planet, which means seventy percent of the planet has got litter on it.”

Annually, at least fourteen million tons of plastic enter the ocean, accounting for eighty percent of marine debris. Some plastic items are, like the Lego, from cargo spills, but many arrive in other odd ways. Kids, for instance, have flushed two-and-a-half million Lego bricks down toilets. Oceanographers say that light plastic debris, like floating Lego bricks, can travel long distances. Eventually, these materials break down into tiny fragments. Many sink to the seabed or are (lethally) ingested by marine animals. Turner calls the plastic at the bottom of the ocean “a ticking time bomb,” and Williams’ book mentions a dead whale that washed up in the Philippines with eighty-eight pounds of plastic in its stomach.

Williams has capitalized on the world’s love of Lego to encourage deeper interest in scientific research. Together with the University of Plymouth, Williams is working on a paper that looks at the spread of the Lego pieces, “both on the surface of the ocean and along the seabed,” she says. Others are getting on board, such as Rob Arnold, an environmental activist who has created a sculpture using half a million plastic pieces collected from Cornish beaches alone.

Williams’ Lego Lost At Sea project “highlights what happens to plastic in the ocean, how long it lasts, how it breaks down, and how far it drifts,” she says — a straightforward way for people to understand the impact of plastic pollution. “Much of the Lego from the spill has been found by people who pick up plastic from beaches regularly, and finding a bit of Lego is seen as a reward.”

The findings are also a record of the age we live in. “A few years ago, we were picking up HP printer cartridges from a cargo spill,” she says. “Now we’re picking up vapes in large quantities, something we’d never really heard of until quite recently.”

Williams calls Lego Lost At Sea a “story without an end.” She writes in Adrift that “it’s a vast jigsaw with millions of pieces still missing. … Sometimes I wonder if millions of years from now, a fossil hunter will take a hammer to a rock and discover a perfectly preserved Lego shark inside. A fossil of the plastic age.”

Recovered Legos are part of an ongoing exhibition at the Royal Museum of Cornwall, UK. Open until November 25.