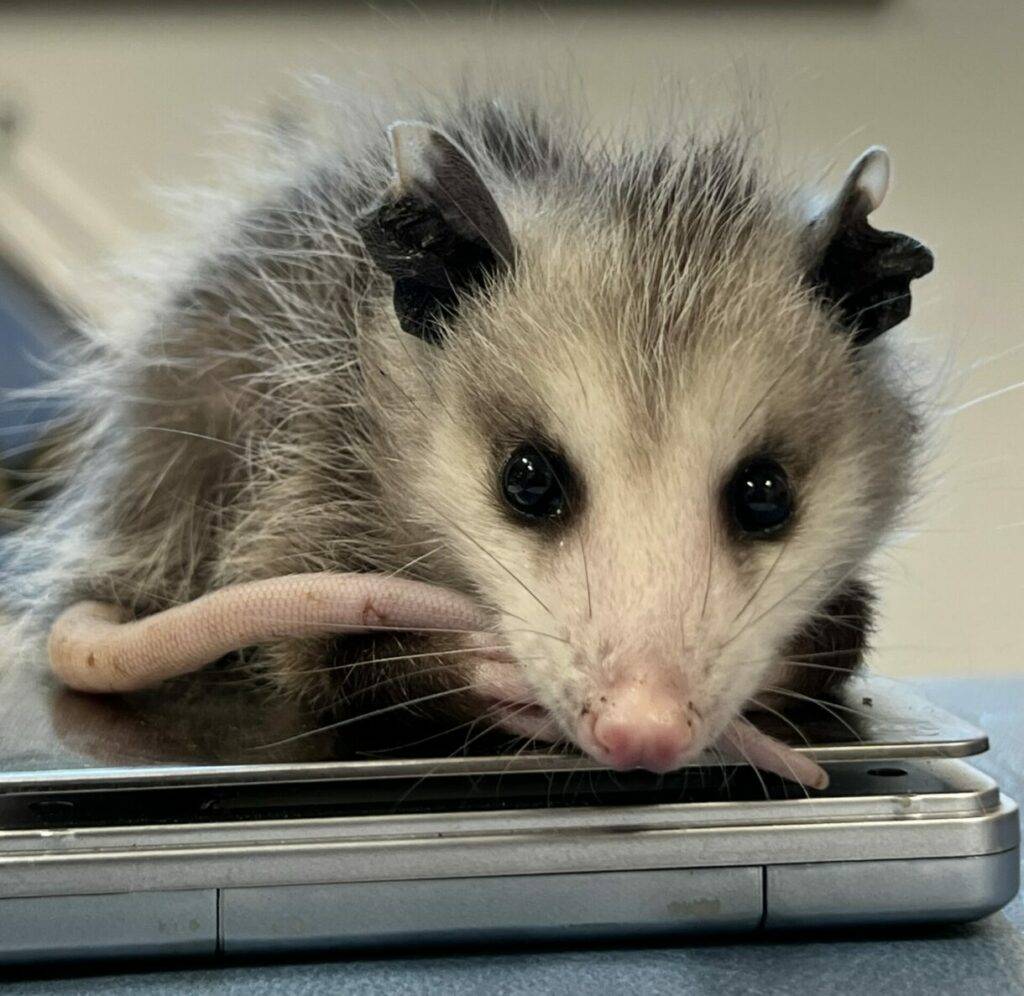

After some much-needed upgrades, the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network is busier than ever.

Until last year, the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network (SBWCN) operated out of a small house and an assortment of sheds and trailers. Hummingbirds and pelicans shared space with skunks and rabbits like raucous siblings in the world’s most taxonomically diverse boarding house.

Now the wildlife rescue and rehab organization, which is busy 24/7 with animal care, feeding, and intake of new patients, has more room to breathe. Its new hospital, opened in 2022, is a 5,400-square-foot medical facility in Goleta, designed to meet the unique and unpredictable needs of injured animals across Santa Barbara and Ventura counties.

“We are an emergency room. We are an orphanage. We are an extended care facility. We are all of these things at once,” says Ariana Katovich, SBWCN’s Executive Director. “Our helpline gets, depending on the year, seven to ten thousand calls.”

Hummingbirds and pelicans shared space with skunks and rabbits like raucous siblings in the world’s most taxonomically diverse boarding house.

When I visited, the hospital was in the bustle of springtime, as the breeding season for wild animals collided with the lawnmowing, tree-trimming, and landscaping season for people.

“We’re in baby season right now, so we’re seeing twenty to forty intakes a day of all different animals,” Katovich told me.

In one room, a team of dedicated staff and volunteers fed a group of miniscule baby rabbits with syringes, speaking in hushed whispers to avoid stressing the high-strung species.

“We get between two hundred and three hundred brush rabbits a year,” Katovich said.

In another wing, an American robin with the tufty eyebrows of adolescence got a similar treatment — it had likely been knocked from a nest as a chick, but was now eagerly perched and awaiting its meal.

“This is our songbird room,” Katovich said. “Seventy percent of our patients are birds — songbirds and seabirds.”

The smallest patients were tiny hummingbirds perched on branches in a mesh cage near the center of the room. “We mostly get Allen’s and Anna’s,” Katovich said. These were Allen’s, and they were quickly getting on a first-name basis with the volunteers in charge of their feeding — every fifteen minutes.

“We feed them a high protein diet, and also nectar,” Katovish said. “And then we give them natural forage to make sure they learn how to get different food sources in the wild.”

Once graduated from the songbird room, feathery patients are moved to outdoor aviaries to prepare for life in the wild. “All these birds are monitored before they’re ready for release: how much they eat, how much weight they’re gaining, their feather quality, their ability to feed themselves, their ability to fly,” Katovich said.

Staff and volunteers busily administer the bespoke diets and meal schedules of other birds in the room, including a Pacific Slope Flycatcher, an Acorn Woodpecker, a Northern Mockingbird, and several California Scrub Jays. “We have to know what these species eat, whether they are an aerial insectivore or ground forager, what their habitat is like, how to set up their enclosure,” Katovich says.

Outside, in addition to the aviaries, there’s a swimming pool filled with recovering ducks and a “raccoon resort” next to an enclosure of curious skunks.

The hospital has rooms for x-rays and surgeries, a climate-controlled room for temperature-sensitive birds, a mammal nursery, and — importantly — a break room.

Outside, in addition to the aviaries, there’s a swimming pool filled with recovering ducks and a “raccoon resort” next to an enclosure of curious skunks. The skunks do occasionally spray the staff, although handling them with care and “knowing the signs” can minimize risk.

Serving an area of more than four thousand square miles of diverse California coastal habitat, the hospital mainly relies on the public to deliver its patients, but a van out front with the network’s logo serves as an animal ambulance when necessary. “We have a volunteer crew that goes out and assists with rescue and transport, Katovich says.

“The thing about Wildlife Rehab is that it’s impossible to know what your day looks like,” Katovich says. “You know what animals you have at the start of the day. You don’t know who you’re going to have by the end of the day. We think things are mapped out and then we get ten seabirds at four o’clock in the afternoon.”

Wildlife hospitals are in a gray area between veterinary care and conservation, a kind of triage in the face of friction between human activity and wild ecosystems. Katovich acknowledged the necessity of broader work like habitat protection, wildlife corridors and other ecosystem conservation, but said, “what we’re doing is mostly mitigating human damage. Animals are attacked by cats, struck by cars, caught by fishing hooks, hit glass windows, and are affected by rodenticide, pesticide or herbicide. We are trying to mitigate the effects of the human environment on these animals.”

The Wildlife Care Network’s expertise comes in handy when wider ecological catastrophes occur: brown pelicans, which were on the endangered species list until 2009, are regular patients. “There was a pelican crisis last summer,” Katovich says. “We had almost 300 birds come to us in a month, in a mass starvation event. We were able to put animals in our seabird room and turn the temperature up to 85 degrees.”

Temperature stabilization is important for seabirds, Katovich says, because their body heat is regulated by the waterproofing of their feathers, which can be compromised when injured or oiled. “Part of living in Santa Barbara is that we have a large offshore oil seep naturally occurring, so animals can get oil on their feathers just by being in the ocean,” Katovich says. And the history of human-caused oil spills in Santa Barbara — including large ones in 1969 and 2015 — means that the ability to respond to oiled wildlife is of pressing local importance.

Like most rehabs, the Wildlife Care Network can’t save all of its patients, and euthanasia is a regular part of the work. Katovich tells me, “Some animals are too injured, or they’re in a significant amount of pain. Rather than have the animal suffer anymore, we are able to give it a peaceful passing. It is a hard part of the work, but that’s the reality.”

“Compassion fatigue hits doctors and nurses and wildlife rehabbers and other caregivers,” she adds. “We see a lot of injuries, we see animals that are intentionally harmed by humans, animals that need to be euthanized. People care so deeply about these animals, and taking care of the staff becomes really important.”

When we entered the center, we donned masks and hospital booties, then dipped our feet in a disinfecting rinse in the foyer. “Biosecurity is key,” Katovich says. Among other concerns, “we have to be very careful that avian flu does not come into the clinic.” For the same reason, many birds have periods of quarantine before being allowed into or out of the facility.

“We have a veterinarian full time here,” Katovich says. “More and more centers are making the stretch like we just did, to build a hospital and have a veterinarian on staff. We do surgeries and exams and advanced wound repairs, and we also have a digital X-ray for better diagnostics. It’s changed here in the last couple years pretty rapidly.”

The conditions of the facility’s California state permit require staff to treat animals like patients and not like pets — no frivolous tours, no feeding from baby bottles, and a rigorous guarantee that the rehab pipeline is working as it should: “rescue, rehabilitate, release,” Katovich says.

The hospital’s mission has a refreshingly narrow scope. “The problems of the world can be so large,” Katovich says. “But if you’re on the beach, and you see an animal that needs help, and you pick it up — call our helpline, or call any helpline.”

“We can talk you through how to handle the animal safely,” Katovich says. “If it’s a hawk, or if it’s a rabies vector like a bat, raccoon, or skunk, we will find you a professional to come in and help rescue it. It helps us prevent wildlife injuries, and then helps the safe rescue of those animals.”

For people outside of Santa Barbara and Ventura, Katovich recommends a site called Animal Help Now, which connects people with emergency wildlife care providers based on zip code. The National Wildlife Rehabbers Association offers a helpful decision tree for what to do if you find injured wildlife.

Philosophically, the hospital is like other medical practices. “What we do is really hopeful work,” Katovich says. “We are addressing an immediate problem. People who find an injured animal, by and large, are pretty panicked about it. They found an animal that needs their help, it’s got a broken wing, or it’s been orphaned, it’s vulnerable. And so we get to see human compassion from a broad swath of the community. It’s really incredible for us to see how many people actually take time out of their day to show concern for wildlife.”

“It never gets boring, I’ll tell you that. There are 220 species a year and we never we never know who’s coming through that door.”

What you can do:

- Be sure that animals actually need rescuing. Katovich stressed that for baby animals, the wildlife hospital is a place of last resort. “We see a lot of birds that come in that people think are in trouble, but actually they’re not. Fledgling birds of many species spend a lot of time on the ground before they’re actually able to fly,” Katovich said. If a bird is brought in by mistake, the center acts fast to reunite it with its family. “If we can keep that animal in with its parents, then that’s the best outcome.”

- “We always encourage people to trim their trees only in the months that end in the letter R,” Katovich said. Landscaping and tree-trimming are a major source of the injuries the hospital treats. Katovich urged care, and appropriate timing for these activities to make sure nesting animals — in tree cavities, on limbs, in gardens and lawns — are safe.

- Avoid rodenticides and glue traps, which both can have unintended consequences far up the food chain.

- Take precautions to prevent the spread of avian influenza — if you use a bird feeder, clean and sanitize it regularly, and avoid feeding wild birds altogether if you keep domestic ones like chickens or ducks.

- Find many more tips for coexisting with wildlife on the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network’s FAQ page.